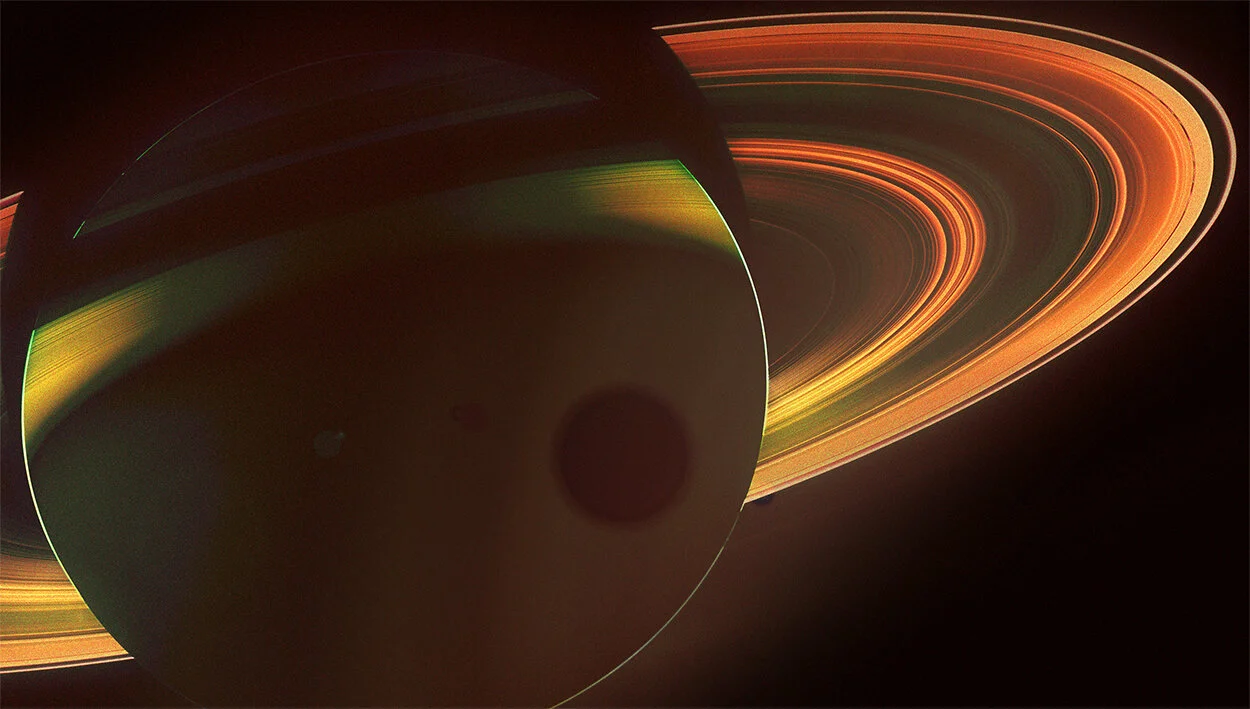

Conjunction

On a rare stellar occasion, two gods, a father and a son, discuss the merits and flaws of the human race.

Source Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute. Photo manipulation by author.

The old man was a haggard, sickly father who’d long since abandoned his sons. His shoulders were hunched inward, but his belly was swollen, veins visibly drawn across his stomach, and it stirred with kicks like the womb of a pregnant mother. He sat at a workbench with a butcher’s cleaver, hacking at a meaty haunch while a vulture looked on. The barn door was open. Outside were his fields; they’d been left unplowed for years but were nonetheless full with grain. His scythe sat in a corner, rustless but always wet, ever sharp.

He paid no mind to the storm outside. Rain beat on his barn’s roof shingles, and its rafters creaked in the wind. A crow flew into the open window looking over his bench, resting on the sill. Its inky feathers burned blue against the light of his oil lamp. It cawed at him.

“Leave — shoo,” the man said, and he waved his cleaver at the crow’s feet. It hopped, landing back on its spot with a flap of its wings. It cawed again and cocked its head, turning. One of its eyes was whitened, blind. The vulture, sitting idly, squawked back — a glottal, halting cry. The butcher stopped his grizzly work, studying the crow and its plumage.

“Leave me, Graybeard.” He gave the haunch another thwack on the cutting board. “This one wasn’t yours.”

The blackbird looked at the meat on the board, eyeing the vulture, then the butcher. It flew off, cawing into the distance as it did.

The man plucked up a piece from the knife. He threw it at the vulture, saying:

“Mimas — here.”

The vulture caught the piece in the air, quickly gulping it down.

The rain continued to pour, and he felt its dampness underfoot as a stream trickled over the foundations of the barn, licking at his toe. Distant thunder rolled, but the man paid no mind. He continued to cut and savored a morsel for himself, gobbling it down like the vulture did.

“Fodder for my stirring sons and daughters,” he muttered, licking his lips. “Stay placid — save those kicks for each other; spare your sweet father.”

Thunder cracked again. This time lightning lit up the barn’s interior like a magnesium flash. He dropped the cleaver and it clanged on the floor. He swore in his mother’s tongue and recomposed himself, picking up the knife again. Looking behind him to the barn’s entrance, he saw nothing but his open fields under gray skies. He turned back to his workbench, wiping the knife down on his apron.

Another lightning flash, this time off in the distance. But its light cast a long shadow across the far side of his workbench and up the wall. He looked over his shoulder to see the silhouette of a tall, built man with streaming locks and a beard. Some kind of bird was on his shoulder — he didn’t bother to see what kind.

“Leave me,” the butcher snorted. “I already told your hoary fortuneteller of a father that I didn’t harvest his bloody einherjar.”

The bearded man strode into the barn as the butcher picked up his cleaver, swinging it down into the meat. It sliced effortlessly, quivering as it struck the board beneath.

“You mistake me.”

Instantly, the butcher recognized the lilt in the man’s voice. It didn’t belong to the crow’s master — this was an Aegean accent. He turned. The man’s hair was dark like oakwood, not blonde, and was thick and curly, his skin olive-colored. His irises were bright pale: electric storm-gray. The bird on his shoulder was an eagle.

The butcher grunted: “Jove, my boy.”

“Saturn,” the god nodded, then adding, “ — father.”

“On what occasion do I owe this visit?”

“Our great conjunction. You are the cosmos’s timekeeper, aren’t you? Surely you out of anyone would know.”

“Ah — our conjunction,” Saturn mumbled, raising an eyebrow at the syllables. He smeared a bloody hand on his apron and fumbled in its pocket. He pulled out a timepiece and flicked it open. Its face held a hundred hands at a hundred different axes, all rotating wildly like the stars in the sky. “How could I’ve forgotten… of course.” He flicked the pocket watch closed and dropped it back in his pocket.

“We’re the closest we’ve been in over half a millenium. Last we spoke, the claymen, our humans, were building houses out of thatched grass and nestled stone. They’d just nearly mastered war and had gone to slaughtering each other en masse.”

“Of course,” said Saturn, grinning from beneath his dirtied beard and mustache. “I’ve barely had to plow my fields since then. Easy harvests.”

“They’re exploring their world. Soon they’ll cross seas instead of just rounding them. They’ll build empires that stretch from one side to another.”

“Sounds like more war to me,” Saturn said, turning back to his cleaver and meat. He noticed Mimas studying Jove’s eagle. “My bales will continue to be thick — which I prefer.”

“But you can’t deny their ingenuity,” the thundergod responded. “Millennia ago, no more than our hands have fingers, they were children with sticks and fire. Now they model themselves after our courts and speculate on our true nature. Don’t you have any opinion on their future? After all, times are few and far between that we get to discuss them so intimately.”

“My opinion,” Saturn muttered, the end of the word cut off by the thwack of his knife on the board, “ — is only as deep as the roots of my grainstock. Only as complex as my hunger. So long as they continue to sacrifice, ignorant of why or not… that is my investment.”

Another thwack as he focused on his butchery. He continued:

“I wonder at your fascination with these creatures, boy. I think even the Aesir only care insofar the offerings are sweet. Speaking of — care for some?”

Old Kronos held out to young, glittering Jove a blood-soaked lump of flesh. Jove’s mouth dipped in revulsion; he waved it away.

“I don’t share your appetites.”

“Of course you don’t.” Saturn threw the piece to Mimas, who gobbled it up like he did the last. “But you have others. These clay men and women are as much your playthings as they are mine. Your choice of play is simply… different.”

Jove’s eagle gave a cry out at the vulture, who squawked back like he had at the crow.

“I’m not here to bicker over our differences,” Jove said, ignoring his father’s insult. “I’m here to discuss their fates.”

“What fates? Different than us gods?” Saturn sneered as his cleaver let loose another thwack on the board.

“You might be disinterested, but I’ve seen their work up close. They may live as long as mayflies, but even now, they’re bursting at the seams of their planet. It won’t hold them for long. Their powers are simple, but the arrangements of their tools grows complicated. Soon they won’t be content to cross the seas enclosing their land… they’ll want to cross vaster seas: the seas that enclose their planet — even the seas that enclose their minds.”

“Damned titans loosened the box and let wildfire run amok,” Saturn said. “Let the clay entertain itself. Who am I — or you — to interfere?”

“You don’t think their empires would impinge on our own, at worst? Or, at best, they might have something worthwhile to add to us as allies?”

Saturn snorted at the word, but said nothing. Jove continued:

“They love, hate, and bicker like us. Their microcosms are merely smaller than ours — but those boundaries grow thin. Sticks and fire were their beginning, not their destiny.”

“You sound like you admire them,” Saturn said. “Are you so quick to get over Prometheus’s duplicity?”

“I admire their ingenuity,” Jove admitted with a shrug, “…their cunning, their persistence — even a god can evolve. Maybe you should consider it as a strategy. It might serve you well someday.”

“I am old,” Saturn growled, letting his cleaver rest on the board. Mimas shuffled on his haystack, still watching the eagle. “I’m older than you. And let me tell you something, Zeus, god of thunder: when Pandora spread her box’s lid, it upset more than the balance I’d instilled since before you were a stone and just as dumb. The rings on my orrery are carefully weighted. The slightest change brings disruption not just to me or you, or even the world of petty humans — the whole cosmos tilts, and worlds with names they barely know will slide off the table. Gods don’t feed off Earth alone, but few places pose such risk. Do you know the balance I had to maintain, that I still maintain? A wayward titan or giant here or there grants a lump of dirt a lit arrow and suddenly they’re jumping rings on my timepiece, planning vacations to Luna for a thrill — “

He slammed his cleaver’s blade into the workbench, its handle erect; Mimas’ wings fluttered as Saturn roared hoarsely:

“If you had a care for either god or human, you’d think like me, and maintain the balance that persists as I do. Instead, you instigate, you whisper sweet nothings in their feminine ears and grant fateful boons by way of your own ineptitude. Your thunderbolts aren’t flashes of genius; they start fires at random. You’re a rebel, a chaosmaker — not a ruler. A king applies laws, he governs. By that standard, your brother Pluto would be a better caretaker than you.”

Jove had his arms crossed, and Saturn was secretly impressed that his son hadn’t lunged at him already. Instead, the Olympian let his eagle off his shoulder, where it flapped its wings and nestled itself on the ground. Saturn added, his tone more even now:

“I am the cosmos’s timekeeper, boy. My accounts are carefully measured. The humans won’t ascend to godhood like you surmise, despite your minor insurrections and naive hope. They are too petty; their own technology eclipses them. If you think their spirits can evolve as fast as their ability to wield various forms of fire, you’re as deluded as they are.”

“Then to what conclusion, this experiment?” Jove asked. “They’ll just consume themselves? Evaporate in a fit of self-annihilation?”

“Of course,” Saturn said, removing his cleaver wedged in the bench. “Gaia will survive even if humanity doesn’t. She is a hardy ground and even more inventive than them. Clay to clay, dust to dust.”

He heard Jove shuffle to the edge of the barn door’s entrance. He could make out his shadow leaning against the frame.

“Say what you say happens. Who will offer sacrifices then? Whose souls will grow as grain in your fields?”

“Gaia is inventive, I already said,” said the harvest god. “Some other clayform will come along while you still walk, I’m sure.”

“And say what you say doesn’t happen. That my naive optimism in them isn’t misplaced — that they do jump your rings, that they cross our skies, and even harness my thunderbolts. What then? What will be the nature of your harvest?”

The vulture squawked at the eagle who stretched his wings wide at the barn’s entrance. Saturn plucked another piece from his board, ripping it between his teeth.

“Why shouldn’t you be worried too, in that case?” He finally replied, chewing skin. “They’ll forget their sacrifices and fancy themselves like the Titans did. On that day I’d imagine you’d come to my side, ready to settle the score.”

Jove nodded, looking across his shoulder to the grain fields outside. Saturn held his cleaver and cut carefully, his knife cutting its way around a thick bone.

“Wouldn’t that be fitting?” Jove said. “They had a genesis once after all, and so did we as gods. That was counted by your orrery even before you made it. Perhaps their fates are set in stone too. I’m sure you could ask the Aesir about that.”

Saturn turned on his bench, letting the cleaver slide in his hand. It nicked the bone.

“Meaning, boy?”

Jove’s glance nestled back on Saturn’s, and his eyes crackled:

“It would be so godlike of them to surpass us in the same way I surpass you.”

The cleaver ripped from the bone and, with barely a thought, flew from Saturn’s hand. Its blade whirled in a tight orbit, headed for Jove’s neck. There was another magnesium flash, and Saturn was blinded briefly. Blinking, the lightning’s afterglow drawn down his sight like a neon vein, he looked for his wayward son.

He didn’t see him. Instead, he saw the oak-colored wings of the eagle in the distance, flying across the grain field. There was a glow beneath its wings on the horizon. Saturn blinked again — the lightning strike had lit the fields aflame. Fire fanned upward even as the storm continued to pour.

He got up from his bench and passed the barn’s threshold. The cleaver was resting just at the edge of the field where he’d flung it, but it had hit nothing but air. It still had fresh blood from the cuttings on his board. He picked it up and wiped it on his apron, looking to either side. There was no one. The eagle in the distance was a fading speck; thunder rolled on.

Saturn turned to go back to his work. He heard the distinctive caw of a bird, but it wasn’t from Mimas inside. He looked up and saw a raven sitting atop his roof’s shingles near the weather vane. It croaked again, turning its head to look at him. Its eye on that side was blind, as white as snow and as blue as ice.

Saturn sneered at it. The raven merely croaked again, then once more, as if in a laugh — then lifted its wings and left. The wind changed as it did, and the vane swung the other way in the storm.

Saturn reached into his pocket to pull out his watch — then hesitated, and stopped. Instead, he grasped his cleaver and went back inside to finish his butchering.